Lesley De'Ath — performer and pedagogue

My involvement with Cyril Scott research stems from around 2001, and from my activities as a performer. At the time I was searching for a large-scale recording project for solo piano—preferably one that involved the issuing of previously unrecorded material for the most part. The object was to raise public awareness of the excellence of much forgotten, long out-of-print piano music from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period that has long held a fascination for me. I knew that an enormous body of material lay languishing on the shelves of libraries worldwide, and that the restricted circulation imposed upon some of this material only contributed to the continuing obscurity of such repertoire.

There are many reasons why a small percentage of the music written for piano over the centuries has become a part of the essential canon, and the vast majority of it has been consigned to oblivion. Few of these reasons have to do with the inherent quality of the writing. My activities, and those of many other pianists, has proven the truth of this time and again, and the world has been greatly enriched by the recording medium in recent decades with the shift in focus away from a few internationally renowned virtuoso performers toward an increased curiosity in the repertory itself.

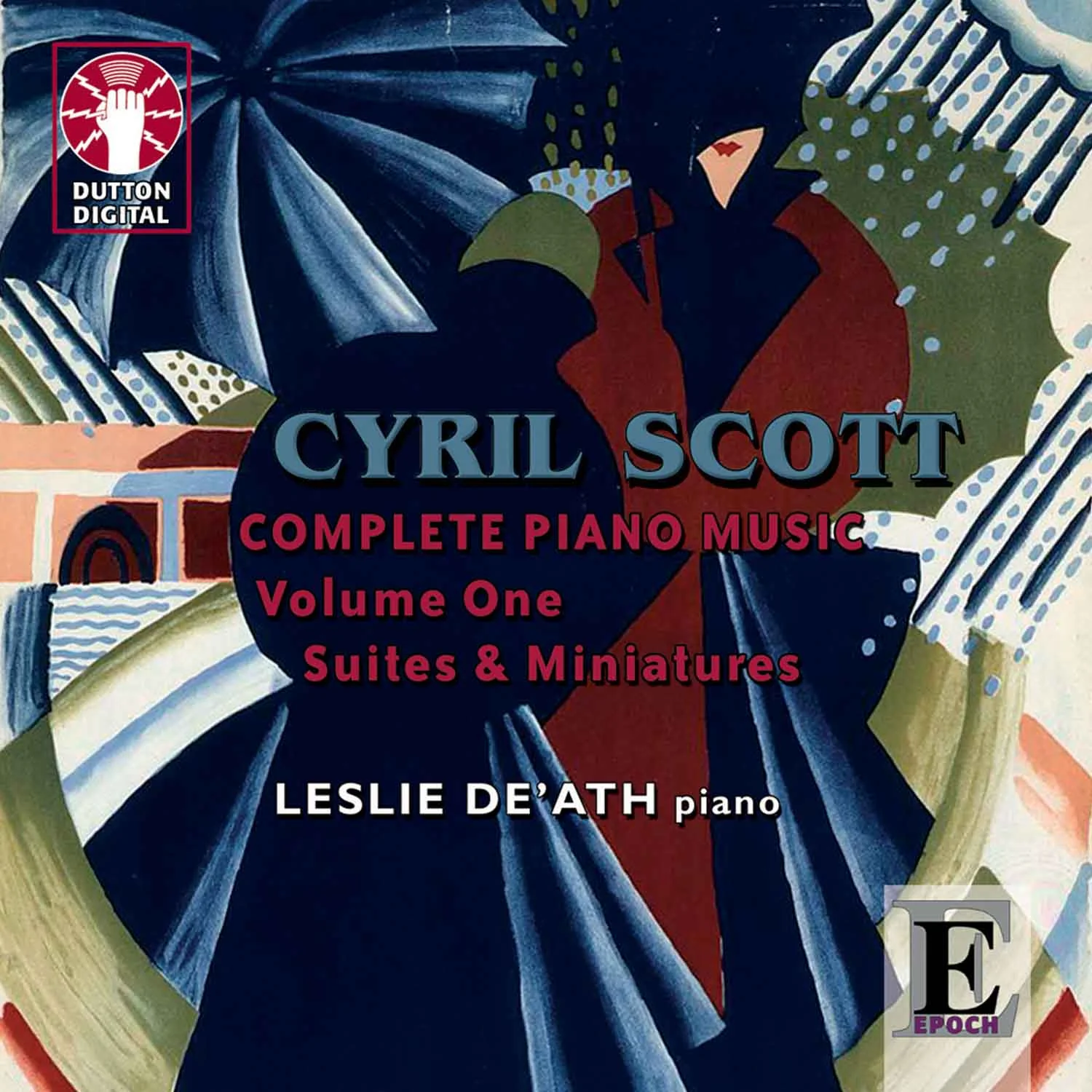

I began with a list of about a dozen composers that I suspected merited such attention. On the top of my list was Florent Schmitt, whose piano music is of great significance in the chronicle of French music from 1900 to 1950. Thus, I recorded a double album of his piano works, intending eventually to expand the project into an intégrale recording of the solo, duo and duet works. Soon into the project, I discovered that Cyril Scott’s son Desmond, and his wife Corinne, lived in Toronto, had a significant career both in theatre and in sculpture, and was the administrator of the Cyril Scott estate. I began to collect and play through as much of Scott’s piano music as I could find, and was shocked to discover just how substantial a contribution he had made to British piano music in the early 20th century—and that almost all of it had at one time been in print. Like most young Canadian pianists, I had grown up knowing of only one piece of his, the ubiquitous Lotus Land which, even in the 1970s, had been on the RCM examination syllabus for decades. The piano music of Ireland, Bridge and Bax, while hardly well-known, had fared somewhat better over the decades than that of Scott, almost all of which went out of print by the 1960s. The other surprise was that Scott’s piano output was more substantial in size than just about any British composer of the time, with the possible exceptions of the equally forgotten York Bowen and Algernon Ashton. Here was at least one major recording project, ripe for the picking!

Not knowing what to expect, I emailed Desmond, introducing myself and saying how delighted I was to find that a direct descendant of Cyril’s was living in Canada, and within easy commuting distance! Desmond was most gracious and interested in my ideas, and although he had initial reservations that the quality of the writing might not be consistent enough to support a complete, multi-CD recording of all the piano works, he did not rule it out. From 2004 to 2009, my primary focus as a performer was the learning and recording of all Scott’s non-concertante piano music—ultimately expanding to over 11 hours of music on 9 CDs. The journey has not just been intensely rewarding musically—in the process I have also gained two very dear friends in Corinne and Desmond. Although Desmond hastens to point out that he is not a musician himself, knowing him personally nevertheless gives me a strong sense of connection to the music and the life of his polymath father. He has been unstinting in providing access to many documents and scores, without which I would not have been able to engage in the level of background research that I felt this project demanded.

The debt also extends to Dutton Laboratories, the enterprising British label that was prepared to take a chance on this music, and on a pianist who had very little reputation as a performer in the British Isles. Enormous gratitude is due to Lewis Foreman, the “artistic arm” of that label, who was intrigued by the idea from the beginning. I had thought it advisable, even strategic, to self-produce the first double-CD on my own in 2004, as evidence of my commitment to the project, and my ability to carry it out. I doubt Lewis fully appreciated at the outset just how sizeable the project would become, when Dutton decided to issue that album commercially the following year.

I had not anticipated that a number of spinoffs would result from my association with Scott’s piano music. There was the trip to Australia in 2004, to read a paper on the piano sonatas for the SIMS Conference. Chandos asked me to reconstruct the Scherzo movement of Scott’s Symphony No.1 for release on CD with Martyn Brabbins and the BBC Philharmonic. My work on the background to the piano works resulted in my own liner notes to each of the Dutton releases. And Desmond and I are involved in the co-editing and authoring of the first full-length book devoted to Scott’s music in almost a century, to be released in 2016. The recordings demanded that I find a duo partner to record the many works for piano duo and duet, and the resulting association with my university colleague, Anya Alexeyev, has been a most rewarding one, that has yielded further recordings, including a double CD of Florent Schmitt duos. I have become familiar with much more than just Scott’s piano music, and have been engaged in the development of a new complete catalogue of works and discography for the upcoming book. I have had occasion to edit several of the unpublished works, the largest of which is the oratorio, Hymn of Unity. My son Graham has become proficient at musical notation programs, and has been involved in the generation of several scores of these unpublished works, for future public access. My work on Scott has broadened to include a particular interest in other British piano music of the time, including two releases of piano solos of Billy Mayerl (who learned much from Scott’s music), the eight ambitious piano sonatas of Algernon Ashton, and most recently, the piano works of Cécile Chaminade, who made a sensation in Britain with her concerts and publications of her own music.

I have come to appreciate the artistic gifts of both Desmond (I am familiar with at least some of the sculptures) and his daughter Amanta (who is also a visual artist and musician). Corinne’s continuing supply of delicious lunches and dinners has been accompanied by her own keen appraisals of Scott’s music, she herself being an organist. And, as a thank-you for the completion of the series of CDs, Desmond presented me with a touching and most welcome and stunningly serendipitous gift: an autograph letter from Florent Schmitt to Cyril Scott, from the 1940s!

The musicologist and Liszt biographer, Alan Walker, once said that it takes a life to study a life. It is beginning to feel a bit like that with my involvement with Scott, now roughly 15 years old! Scott was far more than just a pianist and composer, and involved himself in many non-musical pursuits, authoring over 40 published books. His lifelong friend, Percy Grainger, has received abundant attention in recent decades for his unique life and contributions to music. Scott is arguably an even more complex figure, deserving of the same level of scholarly and performance attention.

Leslie De’Ath is a Canadian pianist, conductor, author, chamber player, vocal coach and accompanist, who enjoys a varied career as both performer and pedagogue.

De’Ath has collaborated with many fine singers and instrumentalists, from Karina Gauvin, Maureen Forrester and Frederica von Stade to Per ien, Alex Klein and Hartmut Lindemann. He has been the pianist with several chamber groups, including the Laurier Trio, Contrasts, and the Poulenc Trio, and has guested with the Penderecki String Quartet and other groups. He has been the keyboard player with the KW Symphony since 1980, and throughout the years of the Canadian Chamber Ensemble's existence, and has performed as soloist with both groups on many occasions.

In recent years he has become involved with the recording medium, and with 25 commercial CDs at present, he has become one of Canada's most recorded pianists. Vocal albums include Schubert’s Winterreise with Daniel Lichti, Hugo Wolf’s Italienisches Liederbuch with Lichti and Catherine Robbin, and a CD of Strauss Lieder with Janet Obermeyer. His instrumental discography includes the complete piano music of Cyril Scott on nine CDs, the eight sonatas of Algernon Ashton, duo piano works of Florent Schmitt, and two recordings of Billy Mayerl favourites, all on the Dutton Epoch label. An album of Victorian cello sonatas, with Simon Fryer, appeared in 2012. His involvement with the recording medium garnered a 2008 Gramophone magazine Editor’s Choice designation, and a Grammy nomination. His first Mayerl CD was chosen as one of the 85 best solo piano recordings available today in the Penguin Guide to the 1000 Finest Classical Recordings.

A primary research interest is the area of phonetics and lyric diction for singers, and he has published many articles in that field as well as in vocal and keyboard literature. He has been an Associate Editor of the Journal of Singing, in charge of the column Language and Diction since 2002.

De’Ath is a Professor in the Faculty of Music at Wilfrid Laurier University, where he has taught since 1979. There he is a studio piano instructor, Music Director of the opera program, and teaches lyric diction and keyboard literature. Over the years he has conducted more than 30 of the Faculty’s opera productions. Hobbies include collecting old and rare musical scores, manuscripts, letters, signatures, and other ephemera, as well as antiques and philately.